With the rapid pace of westernization, economic development, and the increasing number of pets as a member of nuclear families, humans and companion animals share a common sedentary behaviour and unhealthy feeding habits. These insalubrious habits predispose them to lifestyle diseases, also known as non-communicable chronic diseases, which are increasing at an alarming rate in humans as well as in companion animals (Pappachan, 2011; Chandler et al., 2017). One of the most important diseases among them is systemic hypertension in humans and companion animals.

Systemic Hypertension is also known as the silent killer in human medicine. But, it is a newly recognized under-diagnosed disease in veterinary practice that affects the essence and survivability of companion animals (Dixon-Jimenez et al., 2011; Elliott & Brown, 2020).

What is Hypertension?

Hypertension is defined as the persistent high blood pressure (BP) state in the body. Similar to humans, companion animals do suffer from Hypertension. Dogs and cats’ normal systolic blood pressure should be below 140 mm Hg (Acierno et al., 2018).

What is the difference between Hypertension in humans and companion animals?

In humans, most patients suffer from primary Hypertension, i.e., the human patient primarily develops high blood pressure, which causes further damage to the different body organs. In contrast, pet animals used to have secondary Hypertension as the major form of Hypertension. It means that the pet animals suffering from the underlying diseases (most commonly chronic kidney diseases) develop Hypertension. This persistent high BP in the presence of other underlying disease states goes undiagnosed, so veterinarians should routinely practice BP monitoring in clinically diseased and aged dogs.

But, true secondary Hypertension needs to be differentially diagnosed from situational Hypertension, which occurs because of a strange environment (veterinary hospital). This situational Hypertension can be overcome by providing sufficient time (5-10 minutes) for the animals to get accustomed to the hospital surroundings.

What are the different techniques used for blood pressure monitoring?

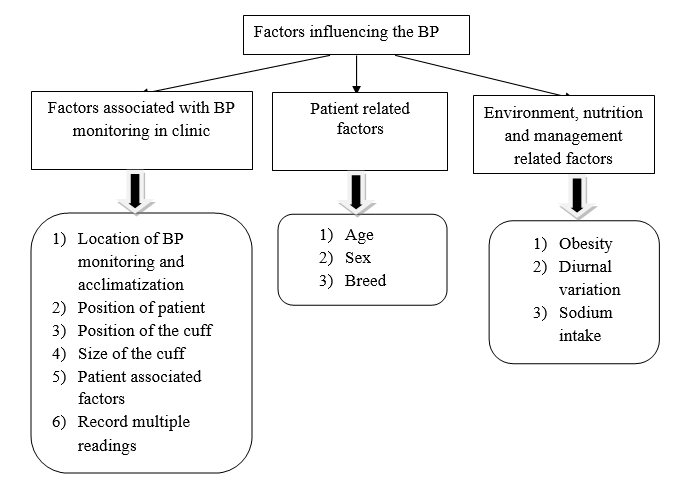

Broadly, there are two methods, i.e., direct/invasive and indirect/non-invasive BP monitoring methods. The direct method is the gold standard for BP monitoring but is of limited clinical use due to its invasive nature and requiring more technical proficiency (Jepson, 2020). Non-invasive BP monitoring devices are the alternative to the direct BP monitoring method because of their non-invasiveness, easy availability, relatively less costly, and less technically demanding. Non-invasive BP monitoring techniques used in veterinary are auscultatory, Doppler ultrasonic flow detector, oscillometry, high definition oscillometry, and plethysmography. The most commonly used out of all these are Doppler (Figure 1) and oscillometric method (Figure 2) (Lloyd, 2018).

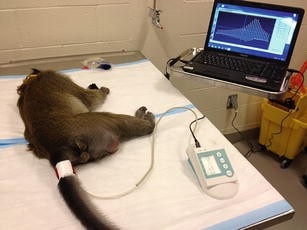

What are the factors that affect blood pressure?

A. Factors associated with BP monitoring in the clinic

- Location of BP monitoring and acclimatization

BP monitoring should be done at a quiet place in the clinical setting, and it is to be performed prior to any invasive procedure to prevent any situational hypertension.

- Position of patient

Lateral recumbency is the suited position for BP monitoring in most dogs and cats.

- Position of the cuff

For Doppler sphygmomanometry, the forelimb is considered the suitable site, and for oscillometry, the tail and hindlimbs are the preferable site (Jepson, 2020).

- Size of cuff

The size of the cuff should be appropriate to avoid false high or low BP readings. The size of the cuff should be 30-40 % of the circumference of the patient’s limb site where the cuff is to be placed (Acierno et al., 2018).

- Patient associated factors

Excessive motion/ movement causes difficulty in taking BP readings via Doppler and oscillometry BP monitoring methods. The patient with peripheral edema or with any structural lesion that causes hindrance in cuff placement is problematic (Jepson, 2020).

- Record multiple readings

ACVIM panel recommends measuring at least 5-7 readings after discarding the first reading (Acierno et al., 2018).

B. Patient-related factors

- Age

In humans, there is an age-related increase in BP. But, in veterinary, there are controversies over the age-related increase in BP (Acierno et al., 2018).

- Sex

In human medicine, the association of BP with the sex of the patient is clearly understood with high BP in male patients. But, in veterinary, there are controversies over the effect of sex on BP (Schellenberg et al., 2007; Surman et al., 2012).

- Breed

There are significant breed differences in the BP of dogs (Acierno et al., 2018).

C. Environment, nutrition, and management-related factors

- Obesity

In humans, obesity, along with aging, is considered to be the most important factor for the current hypertensive epidemic (Hall et al., 2019). While in companion animals, obesity is not directly a risk factor for Hypertension, but it is the comorbidity like chronic kidney disease, cardiomyopathies, and various endocrinopathies that causes Hypertension in obese or overweight animals (Perez-Sanchez et al., 2015).

- Diurnal variation

In humans, there exists a phenomenon of diurnal variation in BP. BP usually dips during sleep. In dogs and cats, this type of diurnal variation does not exist (Syme, 2020).

- Sodium intake

In humans, various studies have described the positive association between sodium intake and BP. But, in cats and dogs, there are not any convincing results about the association between sodium intake and BP (Syme, 2020).

What are the clinical signs and target organ damage concept?

The animals often are asymptomatic except for the presence of signs attributable to the underlying primary disease state, making this disease the most under-diagnosed disease condition in the veterinary. Therefore routine BP monitoring of companion animal patients should be practiced by veterinarians. Renal diseases are the most common cause of secondary Hypertension in canines (Acierno et al., 2018). When persistently high BP causes damage to various organs (brain, eye, heart, and kidney), it is termed as the target organ damage (TOD).

According to the latest ACVIM guidelines, Hypertension is categorized on the basis of risk of target organ damage (TOD) and systolic BP into four types: (Acierno et al., 2018).

i) normotensive with minimal TOD risk when systolic BP is < 140 mm Hg

ii) prehypertensive with low TOD risk when systolic BP is 140-159 mm Hg

iii) hypertensive with moderate TOD risk when systolic BP is 160-179 mm Hg

iv) severely hypertensive when systolic BP is ≥180 mm Hg

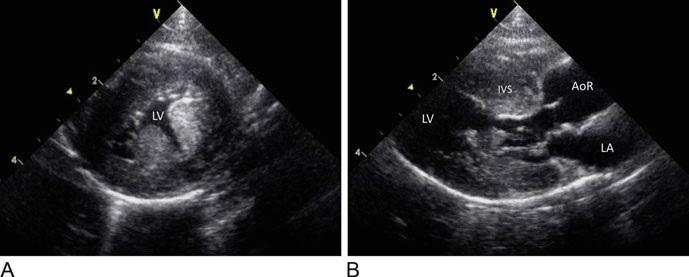

Hypertensive dogs and cats have more severe proteinuria (protein in urine), which correlates with the patient’s survival time (Elliott, 2020). Ocular lesions associated with Hypertension have been described as hypertensive retinopathy and choroidopathy in dogs and cats (Sansom & Bodey, 1997; Maggio et al., 2000). Hypertensive encephalopathy is the term used to describe the deadly complication of high BP in the form of central nervous system dysfunction (Church et al., 2019). The significance of the heart as a target organ of Hypertension has been first recognized as hypertensive myocardial hypertrophy (Figure 3) (Coleman & Brown, 2020). Also, decreased aortic elasticity and increased stiffness in hypertensive human beings as well as dogs (Corda et al., 2020).

Diagnosis and therapeutic management protocols

The therapeutic management of Hypertension in dogs includes treatment of the primary condition along with antihypertensive therapy depending on the degree of TOD (Acierno et al., 2018). The goal of the therapy is to gradually decrease the systolic BP over a period of several weeks. Renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors and calcium channel blockers are the most commonly used drugs to treat Hypertension (Acierno et al., 2018). RAAS inhibitors like angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and aldosterone antagonists are considered as the first line of treatment due to their anti-proteinuric effects where ACEi are most commonly studied in veterinary literature (Acierno et al., 2018). Therefore, ACEi like enalapril/benazepril (0.5-2 mg/kg bwt q 12h) is the preferred initial drug of choice (Acierno et al., 2018). This is followed by calcium channel blockers (CCB) like amlodipine (0.1-0.25 mg/kg bwt q24h) if the animal is refractory to ACEi.

Suggested citation:

Sangwan Tanvika, Saini Neetu, Systemic Hypertension in Companion Animals, The Vet Helpline E-magazine, Category: Veterinary Profession and Continuing Education, Vol XI (2023) ISSN 2454-9282

References

Acierno, M. J., Brown, S., Coleman, A. E., Jepson, R. E., Papich, M., Stepien, R. L., & Syme, H. M. (2018). ACVIM consensus statement: guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and management of systemic Hypertension in dogs and cats. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 32(6), 1803-1822.

Chandler, M., Cunningham, S., Lund, E. M., Khanna, C., Naramore, R., Patel, A., & Day, M. J. (2017). Obesity and associated comorbidities in people and companion animals: a one health perspective. Journal of comparative pathology, 156(4), 296-309.

Church, M. E., Turek, B. J., & Durham, A. C. (2019).Neuropathology of spontaneous hypertensive encephalopathy in cats. Veterinary pathology, 56(5), 778-782.

Coleman, A. E., & Brown, S. A. (2020).Hypertension and the heart and vasculature.In Hypertension in the Dog and Cat (pp. 187-215).Springer, Cham.

Corda, A., Corda, F., Caivano, D., Saderi, L., Sotgiu, G., Mollica, A., …& Pinna Parpaglia, M. L. (2020). Ultrasonographic assessment of abdominal aortic elasticity in hypertensive dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 34(6), 2337-2344.

Dixon-Jimenez, A., Rapoport, G., & Brown, S. A. (2011).Systemic Hypertension in Dogs & Cats. Today’s Veterinary Practice, 1(2), 20-26.

Elliott, J. (2020). Physiology of blood pressure regulation and pathophysiology of Hypertension.In Hypertension in the Dog and Cat (pp. 3-30).Springer, Cham

Elliott, J., & Brown, C. (2020).Hypertension and the Kidney.In Hypertension in the Dog and Cat (pp. 171-185).Springer, Cham.

Hall, J. E., do Carmo, J. M., da Silva, A. A., Wang, Z., & Hall, M. E. (2019). Obesity, kidney dysfunction and Hypertension: mechanistic links. Nature reviews nephrology, 15(6), 367-385.

Jepson, R. E. (2020). Measurement of Blood Pressure in Conscious Cats and Dogs.In Hypertension in the Dog and Cat (pp. 31-65).Springer, Cham.

Lloyd, F. (2018). Blood pressure measurement in cats and dogs: considerations for the clinician. Companion Animal, 23(4), 218-223.

Maggio, F., DeFrancesco, T. C., Atkins, C. E., Pizzirani, S., Gilger, B. C., & Davidson, M. G. (2000). Ocular lesions associated with systemic Hypertension in cats: 69 cases (1985–1998). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 217(5), 695-702.

Pappachan, M. J. (2011). Increasing prevalence of lifestyle diseases: high time for action. The Indian journal of medical research, 134(2), 143.

Pérez-Sánchez, A. P., Del-Angel-Caraza, J., Quijano-Hernández, I. A., & Barbosa-Mireles, M. A. (2015).Obesity-hypertension and its relation to other diseases in dogs. Veterinary research communications, 39(1), 45-51.

Sansom, J., & Bodey, A. (1997).Ocular signs in four dogs with Hypertension. Veterinary record, 140(23), 593-598.

Schellenberg, S., Glaus, T. M., & Reusch, C. E. (2007).Effect of long‐term adaptation on indirect measurements of systolic blood pressure in conscious untrained beagles. Veterinary record, 161(12), 418-421.

Surman, S., Couto, C. G., Dibartola, S. P., & Chew, D. J. (2012). Arterial blood pressure, proteinuria, and renal histopathology in clinically healthy retired racing greyhounds. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 26(6), 1320-1329.

Syme, H. M. (2020). Epidemiology of Hypertension.In Hypertension in the Dog and Cat (pp. 67-99).Springer, Cham.