Introduction:

Goat farming has been age old practice in our country. People of Indus Valley civilization (3300–1300 BC) were familiar with goats in addition to other domestic and wild animals of today. In Rigveda goats were mentioned and kept by Aryans for milk. In the Arthashastra, goat has been described as an important animal for milk. This sector plays an important role in socio-economic development of rural households and rightly referred as Poor man’s Cow owing to multi-dimensional use as meat, milch and wool/fibre animal. However, more than 90% of goats that are found in the developing countries including India remain the primary commodity for meat. Goat rearing in the country is mostly restricted to marginal and small farmers (Figure 1)

Goat is considerable hardy animal which can even survive on multiple unwanted shrubs and trees in even difficult environment, unproductive lands where no other food crop can be grown. Many breeds of goat have potential to multiply extensively owing to the prolificacy potential such as Black Bengal goats. Goats are also required for religious ceremonies and festivals like Id-ul-Azha or Bakar-id to commemorate the sacrifice of Prophet Ibrahim. Goat milk considered to have medical value due to characteristic of the constituents in the milk and recently has been used as constituent in bath soap by leading Institute of goat (Central Institute for Research on Goat) in India.

The goat population in our country has declined by 3.82% over the 18th census of livestock and the total Goat in the country is 135.17 million numbers in 2012. The possible causes of the current trend can be multiple, however important factors responsible includes health constrains in addition to factors like decreasing agriculture land, fellow land and grazing area; change in social dynamics; available choices in selection of animal protein food, etc. Many of these factors are beyond control at individual level or farm level. However health constraints can be targeted and controlled. Amongst many health problem in goats attributing to constraint in goat farming, goat plague or PPR is the major issue affecting farmers and farms.

PPR /Goat Plaque

PPR (peste des petits ruminants) is a most important viral disease of goat capable of heavy mortality and commonly called as goat plague. The other synonyms of the disease are psuedorinderpest of small ruminants, pest of small ruminants, Kata, stomatitis-pneumoenteritis syndrome, contagious pustular stomatitis, pneumo-enteritis complex based on resemblance to rinderpest of cattle, species affected, location and symptoms.In India the estimated annual economic loss due to PPR in goats is around Rs. 5477.48 crore (Singh et al., 2014). PPR is included in list ‘A’ disease of the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), Paris. The list includes those transmissible diseases that have the potential for very serious and rapid spread, irrespective of national borders, that are of serious socio-economic or public health consequence.Thepresence of disease can limit trade and export; import of new breeds; development of intensive livestock production and results in loss of animal protein for human consumption. PPR is very troublesome disease for goat farmers. PPR has high morbidity (80-90%) and mortality (50-80% and extent up to 100%) rate. The disease is more severe in young animals, poor nutrition, and concurrent parasitic infections. Concurrent infections such as contagious ecthyma (ORF), pox may also result in PPR outbreak. Recovered animals have lifetime immunity.

Etiology

The causative virus was first thought to be an aberrant strain of rinderpest virus that had lost its ability to infect cattle. Later molecular studies showed that it was distinct from, but closely related to, rinderpest virus. PPR is an important disease and it has also created problems because of its apparent similarity to rinderpest – the clinical signs of PPR closely resemble those of rinderpest, making differential diagnosis difficult. The history of disease backs to 1942 when first report of PPR came from Ivory Coast (West Africa) by Gorgadonnec and Lalanne. Investigators soon confirmed the existence of the disease in Nigeria, Senegal and Ghana. In 1972 in Sudan, a disease in goats that was originally diagnosed as rinderpest, was confirmed to be PPR. During 1990’s, PPR virus re-emerged. In India first reports of PPR outbreak in 1992 came from Tamil Nadu. China first reported the disease in 2007 and it spread into North Africa for the first time and reported from Morocco in 2008.

The PPR virus belongs to family Paramyxoviridae, genus Morbillivirus similar to Rinderpest virus. The other members of the family include human measles virus, canine distemper virus and the distemper virus of sea mammals. Based on genetic characterization of PPR virus strains organized into four groups; three from Africa and one from Asia. One of the African groups of PPRV is also found in Asia. It may survive at 60°C for 60 minutes, stable from pH 4.0 to 10.0, but can be killed by alcohol, ether, and detergents as well as by most disinfectants.

Susceptible species and transmission:

Principally PPR is a disease of goats and sheep. Comparatively disease is more severe in goats than sheep. Kids >4 months and < 1 year of age are also most susceptible. In endemic areas, most of the sick and dying animals are >4months and up to 18 to 24 months of age. As per one report in captive wild ungulates, American white tail deer is experimentally susceptible. Role of wildlife in transmission is unknown. Cattle and buffalo can seroconvert but do not transmit disease. PPRV antigen has been detected in lions and camels. Pigs have no role in PPR epidemiology. The PPRV does not infect humans.

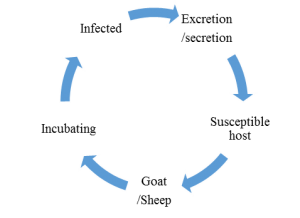

Close contact and confinement favours PPR outbreak. The Virus is present in ocular, nasal and oral secretions and faeces of sick animal (Figure 2). There is no known carrier state.

No conclusive information available if fomites play a role. Fine infective droplets are released into the air from these secretions and excretions, particularly when affected animals cough and sneeze are the source of transmission. Stress is considered as important factor in perpetuating the clinical disease such as transport stress, pregnancy, worm load, pre-existing diseases, etc. Oxidative stress parameters like decrease levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSHPx) also play role in disease pathogenesis. Appearance of clinical PPR may be associated with any of the following:

- History of recent movement or gathering together of sheep and/or goats of different ages with or without associated changes in housing and feeding

- Introduction of recently purchased animals

- Contact in a closed/village flock with sheep and/or goats that had been sent to market but returned unsold

- Change in weather

- Change in husbandry (e.g. towards increased intensification) and trading practices

Pathogenesis and Clinical signs:

Pathogenesis of PPR virus is similar to that of rinderpest in cattle. Virus penetrates the retropharyngeal mucosa, sets up a viremia and specifically damages the alimentary, lymphoid and respiratory system. Death may occur from severe diarrhoea, sometimes hasten by concurrent diseases. Lymphoid necrosis is not so marked as in rinderpest and immunosuppression. This characteristic often makes affected goat succumb to diseases like contagious ecthyma or blue tongue post infection with PPR virus. Reproductive problems associated during the outbreak and post outbreak of PPR has been reported by researchers. PPR causes abortion in pregnant does and there is vulvo-vaginitis in female goats affected with PPR.

The clinical sign of PPR in goats is often fulminating and fatal although apparent infection occurs in endemic areas. Incubation period may range from 2-6 days in field conditions. In acute form, there is sudden onset of fever with rectal temperature of at least 40°- 41°C. The affected goats show dullness, sneezing, serous discharge from the eyes and nostrils. During this stage farmers often think that the animal has developed cold exposure and may attempt to provide protection for cold. In the process goats may be congregated and accentuate the process of transmission. After 2-3 days discrete lesions develop in the mouth and extend over the entire oral mucosa, forming diphtheric plaques (Figure 3).

During this stage profound halitosis (foul smell) is easily appreciable and the animal is unable to eat due to sore mouth and swollen lips. Latter ocular discharge becomes mucopurulent and the exudate dries up, matting the eyelids and partially occluding the nostrils. Diarrhoea develops 3-4 days after the fever and is profuse and faeces may be mucoid or bloody depending upon the damage. Dyspnea and coughing occur later due to secondary pneumonia. Death occurs within one week of the onset of the illness.

Treatment and Control:

No specific treatment is recommended for PPR being viral disease. However, mortality rates can be reduced by the use of drugs that control the bacterial and parasitic complications. Specifically Oxytetracycline and Chlortetracycline are recommended to prevent secondary pulmonary infections. Lesions around the eyes, nostrils and mouth should be cleaned twice daily with sterile cotton swab. Our experience indicates that fluid therapy and anti-microbial such as Enrofloxacin or Ceftiofur on recommended doses along with mouth wash with 5% boro-glycerine can be of benefit in reducing the mortality during outbreak of PPR in goats. Health workers should inspect first the unaffected goats followed by treatment of affected goats. Immediate isolation of affected goats from clinically healthy goats is most importance measure in controlling the spread of infection. Nutritious soft, moist, palatable diet should be given to the affected goats. Provide parenteral energy infusion in anorectic goats along with appetisers.

Immediately measures should be taken for notification of disease to nearest government veterinary hospital. Carcasses of affected goats should be burned or buried. Proper disposal of contact fomites, decontamination is must. Vaccination is the most effective way to control PPR (Figure 4).

Rinderpest tissue culture vaccine was initially used to protect small ruminants and at present is obsolete. Now homologous PPR vaccine is being used. The vaccine can protect small ruminants against PPR for at least for 3 years. Dose of PPR vaccine available in market (Ovilis PPR®; Raksha PPR®) is 1 ml and can be given sub cutaneous route at the age of 4 months. Males and goats kept for more than 3 years may be revaccinated after 3 years. It is important to note that farmers should be asked to avoid providing any stress such as transportation, inclement weather, etc. to the goat for a period of at least 3 weeks post-vaccination.

Please click logo of the companies to learn more about their PPR Vaccine:

Download Global PPR Control Strategy 2015 : PPR-Global-Strategy-2015-03-28

Read previous related posting on Preventive care for diseases in Sheep and Goat.

Conclusion

Goat farming has immense potential to expand. The limitation arising out of animal health problems in goat rearing can be managed by bringing awareness among goat farmers and entrepreneurs regarding major disease/conditions of economic importance such as PPR. Control measures are available and effective; however, implementation on the part of the individual farmers and government needs to have a greener shade.

Download: OIE FAO Advocacy paper 2015 on PPR

Download: PPR Global eradication program ( 2017-2021 )

Download: Document containing Revised Regional Roadmap on PPR control 2014-25 for SAARC Member Countries

Click Here to download the proceeding of National Conference on PPR disease, Nov 28-29, 2014 ( Courtesy: GALVmed )

Published to commemorate:

Download : RecommendationoftheConference

Visit: FAO PPR portal

Visit: OIE PPR Portal