Introduction

Diseases of the digestive tract in ruminants comprise major clinical problems and sometimes, these either remain undiagnosed or fail to respond to medicinal treatment which ultimately results in major economic loss for the farmers. One of the commonly seen conditions in the field which remains undiagnosed is diaphragmatic hernia (DH). Among all ruminants, DH has been found to have a higher occurrence in buffaloes. Buffalo is an important meat animal as well as the major dairy species in India which contributes over 50% of the total milk production in the country

The diaphragm is a dome-shaped musculo-tendinous barrier between the thoracic and abdominal cavity. It separates the thoracic organs like the heart and lungs from abdominal organs like the rumen, reticulum, intestines, liver, and spleen, etc. A diaphragmatic hernia occurs when one or more of abdominal organs enter into the thoracic cavity through a congenital or acquired defect in the diaphragm. Commonly the reticulum is herniated into the thoracic cavity (Bisla et al.2002). It is more prevalent in buffalo than other ruminants due to their indiscriminate feeding behavior as well as the genetic predisposition due to a weak diaphragm. DH is common during pregnancy as the uterus is extended into the abdominal cavity causing pressure on the visceral organs and ultimately, on the diaphragm. (Singh et al,2006)

Etiopathogenesis of Diaphragmatic hernia

- Buffaloes have a comparatively small tendinous portion of the diaphragm resulting in innate weakness which predisposes them to be most affected.

- Increased intra-abdominal pressure may be due to advanced pregnancy or at the time of parturition, tympany, chronic cough, violent fall, etc. ( Singh et al,2006)

- The main cause of diaphragmatic hernia in buffalo has been found to be Foreign Body Syndrome; the presence of potential foreign bodies in the reticulum which leads to weakening and ultimately, rupture of the diaphragm as a sequela of Traumatic reticuloperitonitis. (Divers and peek,2008 )

- Deficiency of minerals in diet leading to pica due to which animals may relish objects with a mineral or metallic taste thereby, ingesting foreign bodies like wire, nails, etc.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on both history and clinical signs. Mostly the animals have a history of recent parturition or in an advanced stage of pregnancy. Affected animals do not respond to medicinal treatment.

Clinical signs

- Recurrent tympany: Inhibition of rumen peristalsis due to reticular adhesions is considered as the main cause of tympany.

- Frothy bloat: Due to the entrapment of reticulum in the thoracic cavity. This leads to distortion of the oesophageal groove, reticulo-omasal opening, and produces hypermotility of rumen which in turn forms frothy ruminal content.

- Animal may show signs of regurgitation at times.

- Partial anorexia with dry faeces containing mucus shreds or no defecation.

- Dyspnoea with open mouth breathing.

- The lactating buffalo shows a significant and sudden fall in milk yield.

- Auscultation: Reticular sound is audible on auscultation of the thoracic cavity, suggestive of diaphragmatic hernia.

Confirmatory diagnosis is made by

a) Ultrasonography

b) Plain or contrast radiography

c) Laparo-rumenotomy

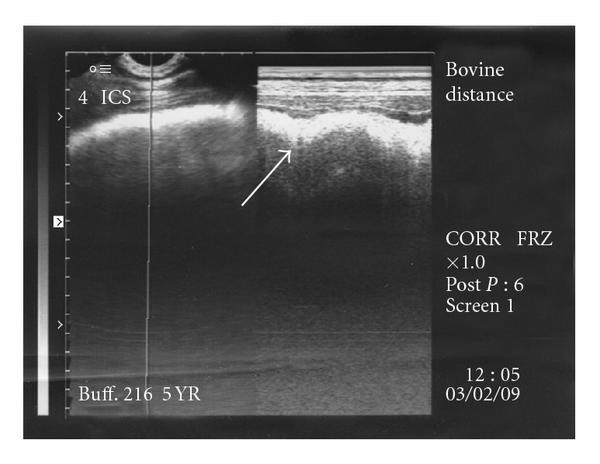

Ultrasonography: Scanning of reticulum motility cranial to 5thintercostal space in standing position is considered confirmatory for diaphragmatic hernia in bovines. Ultrasonographically, normal reticulum appears as a half-moon shaped structure with biphasic contractions of one per minute and the first contraction being incomplete. Reticulum can be located in the thoracic cavity by placing the transducer in the 5th,4th, and 3rdintercostal space at the level of the elbow joint. The transducer is then moved ventrally and reticular contractions are assessed. The presence of biphasic motility in the thoracic cavity on the B+M mode ultrasonogram is confirmatory for Diaphragmatic hernia in bovines. (Athar et al,2010 )

Ultrasonogram showing hyperechoic reticular wall (arrow ) at 4th intercostal space ( Athar et al, 2010 )

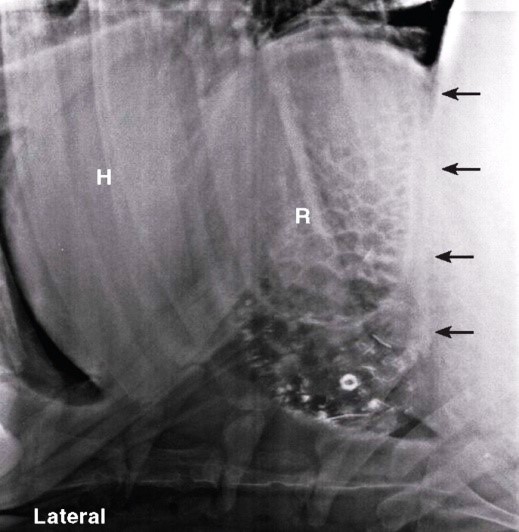

Radiography: Radiographs in right lateral recumbency with forwarding stretched forelimbs at the end of inspiration helps in the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia. ( Athar et al,2010 ) The following findings are present either solely or in combination with others:

- Break in the continuity of the diaphragmatic line.

- A sac-like structure cranial to diaphragm either with metallic foreign bodies or without it.

In some animals, a characteristic reticular honeycomb pattern cranial to the diaphragm is also confirmatory to diaphragmatic hernia.

Fig. 2: Radiograph showing reticulum(R) herniated into the thoracic cavity adjacent to heart (H) with some metallic foreign bodies. Arrows are showing a broken diaphragmatic line ( Kumar and Saini,2011 )

Laparo-rumenotomy: Left flank rumenotomy under local anesthesia in the standing position is a confirmatory diagnostic procedure for diaphragmatic hernia.

Treatment

The only treatment for a diaphragmatic hernia is a surgical intervention which is done in two steps. Apart from being a diagnostic method laparo-rumenotomy, is also a primary step for the treatment of diaphragmatic hernia. In this procedure, penetrating foreign bodies are removed from the reticulum as well as the rumen, and almost three-fourth or complete ruminal content is evacuated. The animal is kept off feed and off water for 24-48 hours prior to surgery and kept hydrated with fluid therapy.

In the second step, diaphragmatic herniorrhaphy is done in dorsal recumbency under general anesthesia. In this procedure, adhesions between the reticulum and diaphragm are bluntly dissected and the reticulum is retracted to its normal anatomical position. The Hernial ring is sutured with non-absorbable suture material mostly with no. 3 silk in lockstitch pattern.

Negative pressure is important to maintain in the thoracic cavity during the surgery. Which can be achieved by connecting a 6-inch long needle with a suction pump and placing it close to the point of elbow in the thoracic cavity. These patients are unable to expand their lungs or thorax to a normal ability may need ventilation support. To provide this, Intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) should perform. A mechanical ventilator delivers a controlled pressure of gas to assist in ventilation or expansion of lungs. Positive inspiratory pressure, ventilation rate, or tidal volume of the ventilator will have to set up according to the patient’s need. After herniorrhaphy, muscles and skin are sutured in a routine manner. It is important to re-establish the negative pressure in the thoracic cavity before complete closure of the surgical incision. Surgical intervention is necessary; if untreated, the diaphragmatic hernia may induce mortality in buffaloes.

Postoperative care

- Adequate intravenous fluid therapy up to a week should be done.

- Parenteral antibiotics and analgesics should be given for about a week.

- Antiseptic dressing of the skin wound at least twice a day till the date of suture removal.

- External support to the incision site with a soft padded pillow-like material should be tied ventrally with a cotton folding cot to prevent the recurrence of the hernia.

- The feed should be given gradually to the operated animal.

Points to keep in mind for farmers

- Prophylactic magnet feeding is an effective alternative to rumenotomy in traumatic reticuloperitonitis cases. All cattle and buffaloes over one year of age should be fed prophylactic magnet to immobilize the metallic foreign body in the reticulum thus preventing its penetration through the reticular wall. After oral administration, most magnets drop firstly into the rumen then move to the desired location in the reticulum following ruminoreticular contraction, where metallic foreign bodies get trapped to magnet and prevent several complications like traumatic reticuloperitonitis, diaphragmatic hernia, a reticular abscess.

- Buffaloes should be kept away from construction sites and grazing fields should be monitored for metal debris.

- The processed feed should always be passed over magnets to retrieve any iron-containing foreign materials prior to being fed to the animals.

- Animals should be given good quality mineral mixture in their daily ration.

Reference

Al-Abbadi, O. S., Abu-Seida, A. M., & Al-Hussainy, S. M. (2014). Studies on rumen magnet usage to prevent hardware disease in buffaloes. Veterinary World, 7(6).

Athar, H., Mohindroo, J., Singh, K., Kumar, A., & Raghunath, M. (2010). Comparison of radiography and ultrasonography for the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia in bovines. Veterinary medicine international, 2010.

Singh, M. R. Fazili, S. K. Chawla, et al., “Current status of diaphragmatic hernia in buffaloes with special reference to etiology and treatment: a review,” Indian Journal of Veterinary Surgery, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 73–79, 2006.

Kumar, A., & Saini, N. S. (2011). Reliability of ultrasonography at the fifth intercostal space in the diagnosis of reticular diaphragmatic hernia. Veterinary Record, 169(15), 391-391.

S. Bisla, J. Singh, and D. Krishanamurthy, “Assessment of oxidative stress in buffaloes suffering from a diaphragmatic hernia,” Indian Journal of Veterinary Surgery, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 77–80, 2002.

J. Divers and S. F. Peek, “Diseases of the body system,” in Rebhun’s Diseases of Dairy Cattle, p. 141, Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2nd edition, 2008.