Transition period and its importance

Transition period is defined as the four weeks prior and post calving, and is most crucial period in productive cycle of dairy cows, characterized by greatly disturbing the homeostasis and manifests in increased risk of disease. Transition is to overwhelm the important physiological, metabolic and nutritional changes occurring during this period. It is the turning point in the productive cycle of cows from one lactation to next. There occur several profound physiological changes that modifies her metabolism drastically. Increasing demands of the fetus, development of the mammary glands and synthesis of milk constituents are responsible causes for these changes. Their effective management is of prime importance and serves a major platform to boost cow health, milk production, reproductive potential and thereby profitability.

The transition mismanagement can precipitate the conditions that are often intricate, inter-related and include:

- Hypocalcaemia and downer cows

- Hypomagnesaemia

- Fatty liver and ketosis

- Udder oedema

- Abomasal displacement

- Retention of fetal membranes (RFM)/metritis

- Poor fertility and poor production.

Intricate homeostatic links between metabolic processes and transition feeding focus mainly on control of milk fever to an integrated nutritional approach that optimizes:

- Rumen function

- Energy metabolism

- Protein metabolism

- Calcium and bone metabolism and

- Immune function.

The following hormones influence the initiation of lactation and are associated with profound metabolic changes.

- Insulin and Glucagon

- Thyroid hormone

- Progesterone and Oestrogens

- Prolactin and Placental lactogen

- Glucorticoids and Somatotropin

Adaptive hormonal changes to lactation before calving include:

- Increased lipolysis (breakdown of fats)

- Decreased lipogenesis (fat synthesis)

- Increased gluconeogenesis (glucose synthesis)

- Increased glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen to provide energy)

- Increased use of lipids and decreased glucose use as an energy source

- Increased mobilization of protein reserves

- Increased absorption of minerals and mobilization of mineral reserves and

- Increased food consumption and increased absorptive capacity for nutrients.

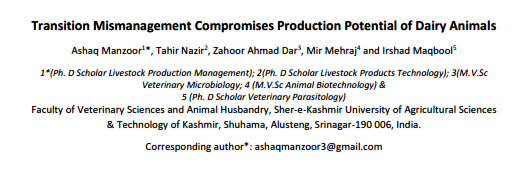

Body condition score

Body condition gives the subjective assessment about the energy reserves the animal has gained over the preceding weeks/ Months of feeding. Excessive loss of body condition (> 1.0 point) after calving has adverse effect on milk production, reproductive and health of the animal. The desirable body condition score in physiological stage of lactation are shown in table-1

Managing the transition period (approach to transition feeding)

Cows should be managed to achieve following objectives:

A.Decrease ruminal disruption:

- Rumen disruption can be prevented through adaptive process which involves the elongation of ruminal papillae and an increase in absorptive area of the papillae

- Full development of ruminal papillae takes longer (3 to 6 weeks).

- Changes to rumen microbial populations (7 to 10 days).

- Lactic acid utilizing bacteria, including Megasphera elsdenii, Selenomonas ruminatum and Vionella spp, produce propionate from lactate, thereby nullifies the sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA) and lactic acidosis as promised by feeding high starch diet.

- Introduction of fibrous diet enhances papillae growth.

- However, rumen pH of less than 6.0 does not favour fiber digestion and DMI gets lowered in subclinical acidosis.

B.Prevent lipid mobilization disorders:

- Careful attention should be given to minimize the depth and length of negative energy and protein balance

- The demands for amino acids, fatty acids and glucose by the feto-placental unit and the mammary gland combined causes a mobilization on body fat and protein. This is prevented through increasing the energy density of the diet.

- Introduction of protein concentrates like mustard cakes, GNC, Cotton seed cakes.

- Body condition score at calving is a major determinant of the calving to first estrus interval, with cows in higher body condition displaying estrus earlier, herd’s submission rate and in-calf rate. For each 0.5-1-unit change in BCS between calving and AI there occurs 10-15% decline in conception.

- Provision of glycerol (100 mg twice daily for 2-3 days), propylene glycol (200 mg twice daily for 2-3 days), sodium propionate (100-200 g once daily for 3 days), sodium lactate and calcium lactate@ 1 kg initially followed by 0.5 kg daily for 7 days as maintenance dose can prevent negative energy balance driven ketosis.

Energy intake restrictions:

The diets are designed to increase feed intake and to control the decrease in dry matter intake as often observed before calving, through feeding diets containing chopped straw having a high fibre, low energy (about 9MJ) and 13% crude protein. This approach may increase the sensitivity of cattle to insulin release around the time of calving following high levels of feeding. Cows in higher body condition score have marked decreases in appetite, whereas cows in BCS <3.5/5 have less decline.

Dietary Cation Anion Difference (DCAD)

- Diets high in sodium and potassium and low in chlorine and sulphur increases the incidence of milk fever, vise-versa.

- Increasing potassium in the diet causes hypocalcaemia.

- Magnesium plays a protective role in milk fever, independent of DCAD.

- Increasing phosphorus concentrations increases milk fever risk, independent of DCAD.

- Commercial supplements containing HCl overcomes the milk fever

- Feeding of ammonium chloride @ 23-25 g over 3 weeks prior to parturition and increasing it to 100g/day at parturition orally twice a day prevents milk fever.

- Urine pH below 5.5 depicts over acidification requires increase in DCAD. Urinary pH over 6.5 reflect inadequate acidification suggesting DCAD value need to be lowered.

- Prevent DCAD by using 500-1000g of a commercial mineral acid feed product (e.g. BioChlor / SoyChlor).

Need for calcium

- At parturition there is a sudden increase in the cow’s calcium requirements for colostrum (2-3g Ca/L) and milk (1.22-1.45g Ca/L) requiring a 2-4-fold increase in calcium availability. Loss of blood calcium to milk may exceed 50g per day. Cows can only afford to lose approximately 50% of circulating blood calcium reserves before a hypocalcaemia is precipitated. The amount of calcium available from bone deposits is limited. Therefore, increased absorption of calcium from the gut is critical to maintaining blood calcium. Otherwise, a gateway disease (milk fever) is evident, which would accompany with eight or more cases of sub-clinical disease.

- Calcium level of diet should not be above 100 gm as it suppresses calcium retention mechanism. 1 gm/45 kg body weight replenishes the calcium level. Diet containing less than 20 gm of calcium per day should be fed for atleast 7-10 days prior to calving and diet containing <80- 100 gm/day of calcium throughout dry period prevents milk fever.

- Calcium drenches and boluses can aid in the prevention of milk fever if given within 12 hours of calving and continued for several days after calving. Rate of administration should be at level of 10-20 drops/minute. Calcium induced disrhythmias can be prevented by intravenous administration of atropine sulphate. Cardiotoxicity can be antagonized by 10% magnesium sulphate 100 to 400 ml injection.

- Complex situation of hypomagnesemic hypocalcemia can be prevented by administration of 200-350 ml calcium-magnesium-orogluconate I/v. followed by S/c. for rest od dose.

- Oral Calcium gel dosing (50% calcium chloride) prevents milk fever. Schedule for same is prior to calving (1 dose), at calving ( 1 dose ), 12 hours post calving( 1 dose) and 24 hour post calving (1 dose)

Need for phosphorus: More than 80 gm/day predispose to milk fever. Intake of 35 gm/day prevents milk fever. Calcium phosphorus ratio should be 1:3.3

Vitamin D

Vitamin D helps in the regulation of calcium and control of milk fever risk.

- Injection of 1–α cholecalciferol (e.g. Vitamec D3 injection R) between 2 to 8 days before anticipated calving can provide an exogenous source of vitamin D. A dose of 1 million units for every 45 kg body weight prevents milk fever. The timing of the injection is important to ensure that calcium uptake is not subsequently depressed by premature stimulus of calcium uptake.

- 1–α cholecalciferol fed orally may reduce risk of milk fever by stimulating calcium uptake.

Microminerals

Dietary supplementation of Chromium ( Cr ) during the pre-calving period may reduce insulin resistance and subsequently decrease plasma NEFA (plasma non-esterified fatty acids ), liver triglyceride levels and improve glucose tolerance, which may result in improved productivity in the post-calving period.

Rumen modifiers

Rumen modifiers (sodium monensin and lasalocid) act directly on rumen microbes, altering the balance between the different populations and the proportions of the volatile fatty acids (VFAs).

Avoid immune suppression through:

- Provision of balanced diet

- Vitamin supplementation

- Ionophore introduction

- Antibiotic provision.

General feeding management during transition period of high yielding dairy animals

- Feeding dairy animals on leguminous or a mixture of leguminous and non-leguminous and supplementation with concentrate is more economical as compared to feeding them on crop residues and concentrates.

- Good results are obtained by feeding a ration that derives 30 to 40% of the feed units from grains and 60-70% from forages.

- The digestibility of the ration on dry matter basis for high producing dairy animal should be over 70 percent.

- The cows should be fed minimum of four times a day at 6 hours intervals. Each feeding should comprise both grain and forage

- From 7th month of gestation cows should be fed 1 to 2 kg concentrate feed in addition to their nutrient requirement. The cows may be made to gain 20-25 kg body weight during this period.

- The cow must calve in relatively fat condition and so they must be on a fattening ration for the last two months of the dry period (A 10 kg milk producer, must gain 500 g / day in last two months of dry period

- For challenge feeding: 2 weeks before expected date of calving, start feeding ½ kg of concentrate mixture increases this amount by 300-400 g daily until the cow is consuming ½ to 1 kg concentrate for every 100 kg body weight.

- For maximizing income, the dairy animals must be fed individually, according to their individual milk production and nutritional requirements. Liberal feeding is necessary for continued high production and its persistency throughout the lactation.

- An abundant supply of clean drinking water must be provided all times. It is most essential feed ingredient

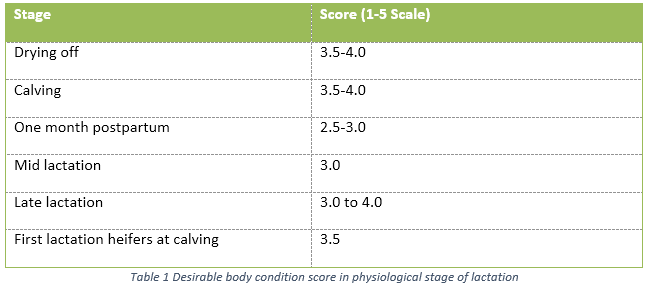

Table 2 highlights the recommendations for dry period and post parturition (1-2 months)

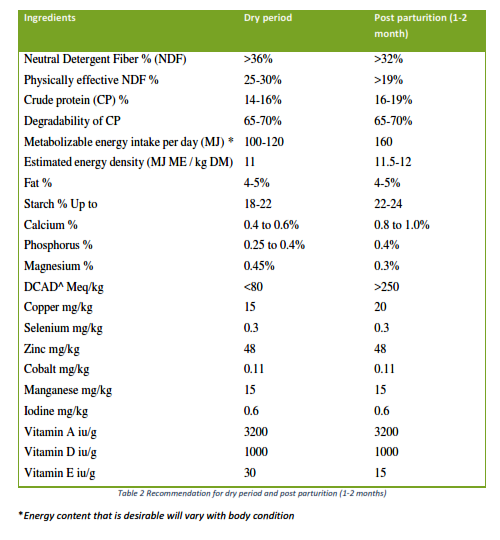

Table – 3 highlights the targets for cow health problems (expressed as percentage of cases of calving cows within 14 days of calving).

Potential risks from improving transition cow nutrition

- Increases the risk of mastitis.

- May impact negatively on colostrum quality

- Increases calf birth weight and dystocia incidences.

However, these adversities are far overwhelmed by the benefits of an integrated approach to transition cow nutrition.

References

Chakrabarti, A. 1988. Metabolic diseases. Text book of clinical veterinary medicine, Ist Edition. pp. 563-614

Drackley, J. K. 1999. Biology of dairy cows during the transition period: the final frontier? Journal of Dairy Science, 82: 2259-2273.

Goff, J.P., and R.L. Horst. 1997. Physiological changes at parturition and their relationship to metabolic disorders. Journal of Dairy Science, 80: 1260-1268.

Grum, D. E., J. K. Drackley, R. S. Younker, D. W. LaCount, and J. J. Veenhuizen. 1996. Nutrition during the dry period and hepatic lipid metabolism of periparturient dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 79: 1850-1864.

Hayirli, A., R. R. Grummer, E. V. Nordheim, and P. M. Crump. 2002. Animal and dietary factors affecting feed intake during the prefresh transition period in Holsteins. Journal of Dairy Science, 85: 3430-3443.

Holtenius, K., S. Agenas, C. Delavaud, and Y. Chilliard. 2003. Effects of feeding intensity during the dry period. 2. Metabolic and hormonal responses. Journal of Dairy Science, 86: 883-891.

Reynolds, C. K., P. C. Aikman, B. Lupoli, D. J. Humphries, and D. E. Beever. 2003. Splanchnic metabolism of dairy cows during the transition from late gestation through early lactation. Journal of Dairy Science, 86: 1201-1217.