Personal opinion of

Dr Miftahul Islam Barbaruah

Candidate no. 51, VCI Election 2024

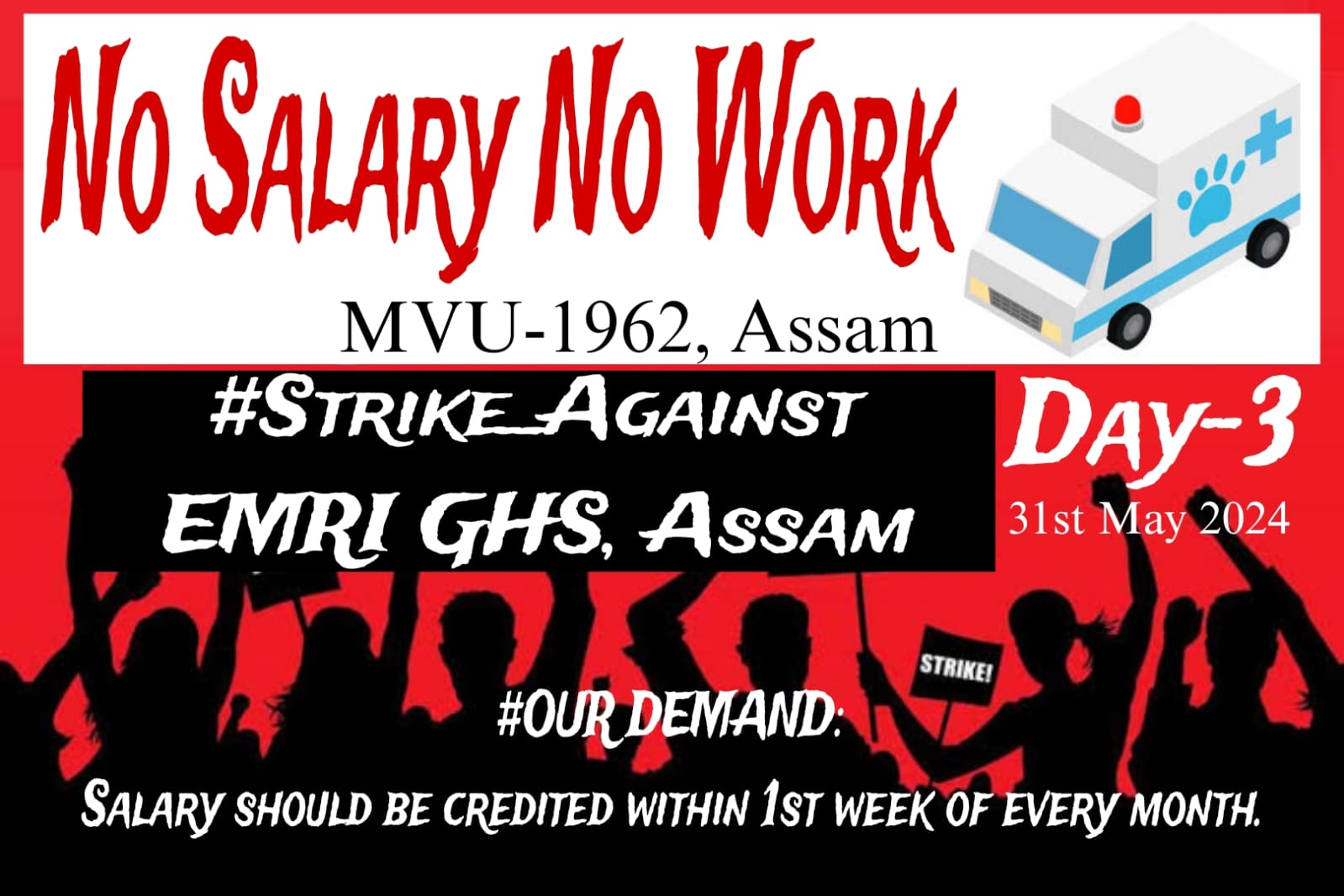

Many veterinarians in India working for the public-funded MVU (Mobile Veterinary Unit) scheme managed by contracted private parties are not getting decent regular salaries and a conducive job environment. Though the government’s core aim is to develop public-private partnership (PPP) arrangements to run the operation, in the true sense, it’s not a PPP. The World Organization for Animal Health defines PPP in the veterinary domain as follows:

“A Public-Private Partnership is a joint approach in which the public and private sectors agree on responsibilities and share resources and risks to achieve common objectives that deliver benefits in a sustainable manner.”

As per my understanding, a contracted company under the scheme neither contributes any resources nor shares the risk of the initiative to achieve the common objective of delivering emergency curative care benefits to animal owners.

Veterinarians engaged in grant-dependent initiatives will always risk losing their jobs when there is a public finance constraint. The current problem of not adhering to the fixed salary norm and delayed salary release is a common financial problem observed in grant-dependent schemes. At best, veterinarians working for MVU ( many of whom are in the prime of their youth) can take this scheme as a stop-gap arrangement to search for better opportunities.

Public veterinary services need to focus more on public good functions, e.g., disease control, food safety, trade facilitation, etc., than curative care. As such, I am not questioning the paradigm change in the policy approach of outsourcing curative services. However, we need to assess the ground realities. MVU in real PPP mode is not feasible in many interior remote areas. It can be managed in interior rural regions only through continuous substantial grants.

Alternatively, the government of India / state governments should strengthen its official workforce with mobile vehicles for publicly funded curative services exclusively targeted at areas where private services are not feasible. By building the capacity of local organizations to assist in primary care and through service aggregation at the last mile, one can minimize the cost of public curative service delivery in such areas. It is also possible to reduce the cost of service delivery by focusing investment on core service-related facilities with optimum use of existing civil infrastructures. In the long run, services in these areas should build local capacity for bio-security enforcement, preventive care, and improved farming practices to minimize the need for emergency services.

Public funding of MVUs that operate in economically viable cluster areas with subsidized services can prevent veterinarians from pursuing entrepreneurial initiatives, e.g., Agri-clinics. Designed vouchers or direct cash transfers can help needy / BPL farmers in viable clusters avail themselves of private services offered by agri-clinics managed by veterinarians. Government services in economically vibrant areas can focus entirely on regulatory, trade, and development management, leaving curative care provision to private parties with regulatory oversight.

Our limited focus on enhancing veterinarians’ employability and career mobility has led to the situation we are experiencing with veterinarians working with MVUs.

The management of MVU is under the purview of public Veterinary Services and the companies implementing it. The Veterinary Council of India (VCI) and State Veterinary Councils (SVCs) can look into the conditions under which veterinary personnel employed by the scheme are providing services and if such services are up to the standards. As stated above, VCI can also facilitate the skilling / re-skilling needs of veterinarians working in such schemes to help them find remunerative employment or initiate viable private practice.

Following are my suggested 5-point action areas:

- Complete the scheme mapping with the Public Finance Management System (PFMS) to ensure the smooth release of earmarked grants to companies.

- Strict enforcement of norms related to the salary for veterinary personnel and release of additional guidelines ( in consultation with state veterinary service associations ) to ensure mentoring by senior government veterinarians and a conducive work environment for contracted personnel.

- The constitution of an expert panel is needed to conduct an early evaluation of the MVU scheme and explore how it can best be shaped as a true PPP for long-term sustainability (beyond the current promised five-year grant support for the central and state budget).

- Plan investments in continuous skill training of current MVU personnel ( for the remaining period of the MVU contract) to prepare veterinary personnel for better private job opportunities with MVUs managed in proper PPP mode and also for the entrepreneurial journey as a clinician or consultant.

- Conduct a workforce assessment and a strategic planning exercise to re-design state/region-specific public-funded emergency and curative services for interior areas where PPP is not feasible.

Click here to visit Dr. Miftahul Islam Barbaruah’s VCI election campaign webpage to read his other views.